Last partial update: September 2019 - Please read disclaimer before proceeding

We need to look after our children.

‘The health and wellbeing of young people is a critical measure of a society for two reasons: in moral terms, how well a society cares for its weak and vulnerable is a measure of how civilised it is; in more pragmatic terms, a society that fails to cherish its young, fails. It’s as simple as that.’

Richard Eckersley, Australian scientist and author.

This section looks at illness that occurs in children and how to best to prevent it. The other important section to read regarding effectively nurturing children is the section on parenting, which is essential reading.

Parenting - Bringing up healthy children who become healtrhy adults

Parenting is the hardest task on earth but can be the most rewarding. Developing beneficial habits during childhood is fundamental to becoming a healthy and happy adult and this pretty much depends on parents teaching. The best way they can do this is to live them themselves. What needs to be taught / demonstrated in a child's home? 'Only' five things;

- Teaching ways to solve problems to give maximum benefit.

- Healthy eating and maintaining a healthy weight

- Exercising regularly to gain significant physical benefit

- Showing love and respect in relationships with relatives, friends and with members of the broader community.

- Avoiding addictive substances through avoiding harm from alcohol use and avoiding completely tobacco and illicit drug use.

The only other thing that then needs to be done is to help children find something they love to do that will provide purpose in life and hopefully make them a living. A headmistress I know said, in one of her end-of-year speaches, that if she could get all the children in her school to love and be really good at just one thing her job would be done.

And role modelling all the above for their children will make parents happier too.

Patrenting is covered in much more detail in the section on Parenting.

When does most illness occur

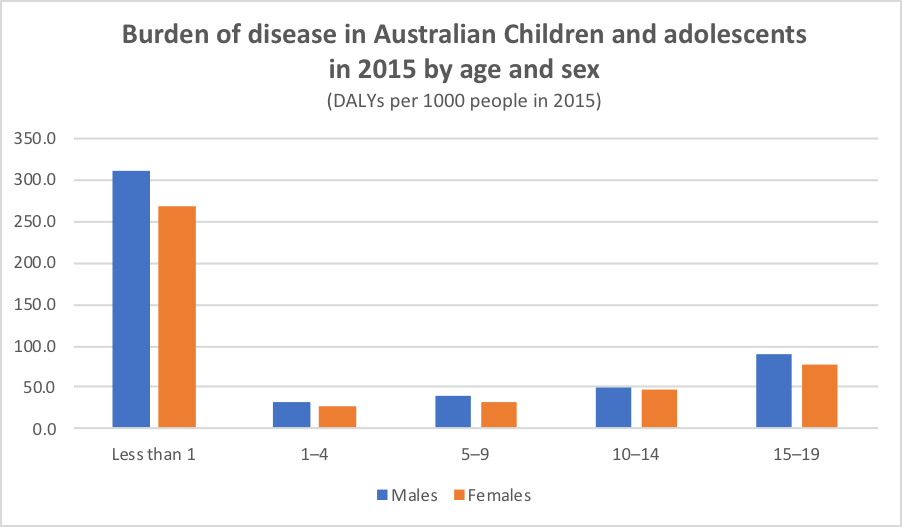

The graph below highlights a very important point. Most of the disability in childhood occurs during foestal development and at birth. Pregnancy and childbirth are a critical stage of life.

Source: Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: 2015.

Identifying preventable childhood illnesses

The causes of childhood illness are fundamentally different to those responsible for adult illness. However, like adult illness, many are preventable. The burden of disease caused by childhood illnesses in 2011 is shown in the table below.

Burden of disease caused by childhood illness in 2015 - Age 0 to 15

|

||

Important illnesses in children

|

% of total burden of disease in boys |

% of total burden of disease in girls |

Pre-term birth / low birth weight |

10.3 |

7.4 |

Anxiety and depression |

8.3 |

9.8 |

Asthma |

7.5 |

7.4 |

Birth trauma and asphyxia |

4.1 |

5.6 |

Upper respiratory tract infections |

3.0 |

2.4 |

Autism spectrum of disorders |

3.7 |

|

Source: Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: 2011. |

||

Because the causes of illness vary significantly within childhood, the causes are broken down into age subgroups. The information in these tables is more recent, 2015.

Burden of disease caused by childhood illness in 2015 - Age Under 1 yr

|

||

Important illnesses in children Under 1 year of age

|

% of total burden of disease in boys |

% of total burden of disease in girls |

Infant and congenital conditions (Mainly preterm and low birth weight, birth trauma and asphyxia, SIDS and cardiovascular abnormalities |

81.0 |

78.0 |

Infectious disease |

5.2 |

6.1 |

Neurological conditions |

4.4 |

3.7 |

Cardiovascular conditions |

1.2 |

2.6 |

Blood and metabolic disorders |

0.7 |

1.1 |

Cancer |

0.8 |

0.5 |

Source: Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: 2015. |

||

Burden of disease caused by childhood illness in 2015 - Age 1 to 4

|

||

Important illnesses in children 1 to 4 years of age

|

% of total burden of disease in boys |

% of total burden of disease in girls |

Injuries / accidents |

20.2 |

15.5 |

Mental health disorders including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism and depression |

14.6 |

10.6 |

Respiratory disease (mostly asthma and infections) |

13.9 |

12.9 |

Infectious diseases |

12.1 |

14.3 |

Infant and congenital diseases |

8.9 |

7.2 |

Neurological diseases |

7.0 |

8.2 |

Cancers |

5.9 |

6.4 |

Blood and metabolic conditions |

5.4 |

8.5 |

Source: Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: 2015 |

||

Burden of disease caused by childhood illness in 2015 - Age 5 to 9

|

||

Important illnesses in children 5 to 9 years of age

|

% of total burden of disease in boys |

% of total burden of disease in girls |

Mental health disorders including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism and depression |

36.6 |

29.4 |

Respiratory disease (mostly asthma) |

16.8 |

15.3 |

Injuries / accidents |

8.9 |

8.7 |

Oral disorders (tooth decay) |

6.1 |

7.3 |

Cancers |

6.0 |

5.6 |

Musculoskeletal conditions |

4.4 |

6.2 |

Infant and congenital diseases |

4.3 |

3.5 |

Infectious diseases |

3.7 |

5.3 |

Neurological diseases (mainly epilepsy) |

3.5 |

7.0 |

Source: Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: 2015. |

||

Burden of disease caused by childhood illness in 2015 - Age 10 to 14

|

||

Important illnesses in children 10 to 14 years of age

|

% of total burden of disease in boys |

% of total burden of disease in girls |

Mental health disorders including amxiety and depression, conduct disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder & autism in boys and eating disorders in girls |

36.5 |

33.3 |

Respiratory disease (mostly asthma) |

14.1 |

12.9 |

Injuries / accidents |

11.1 |

9.3 |

Skin disorders (mainly acne) |

8.3 |

11.1 |

Musculoskeletal conditions (back problems including scoliosis) |

7.6 |

9.2 |

Neurological diseases (mainly epilepsy) |

5.3 |

4.8 |

Infant and congenital diseases |

3.7 |

2.9 |

Oral disorders (tooth decay) |

3.4 |

3.6 |

Infectious diseases |

2.1 |

3.2 |

Source: Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: 2015. |

||

Burden of disease caused by adolescent illness in 2015 - Age 15 to 19 |

||

Important illnesses in adolescents 15 to 19 years of age

|

% of total burden of disease in boys |

% of total burden of disease in girls |

Mental health disorders and substance abuse (Mainly suicide in males and anxiety in females) |

33.3 |

36.8 |

Injuries / accidents |

26.9 |

14.6 |

Musculoskeletal conditions |

7.8 |

8.7 |

Skin disorders |

7.7 |

8.6 |

Respiratory disease (mostly asthma) |

6.6 |

8.0 |

Neurological diseases |

3.7 |

4.3 |

Oral disorders (tooth decay) |

3.4 |

3.0 |

Infant and congenital diseases |

2.7 |

1.9 |

Infectious diseases |

1.4 |

1.8 |

Source: Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: 2015. |

||

There are a few noticeable differences between illness in boys and girls. Importantly, boys experience about 57% of burden of disease from all childhood illness and girls only 43 per cent. Significant contributors to this difference are accidental injury, with boys experiencing 64 per cent of all accidental injury burden of disease, and attention deficit disorder, with boys experiencing 72 per cent of the burden of disease from this condition.

The halving of the infant mortality rate in Australia over the past two decades, from 9.6 per 1000 live births in 1983 to 4.8 in 2003 shows how successful attention to preventative health issues can be, with initiatives in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and accident prevention being the main contributors to this fall. (The SIDS rate has fallen by well over half in the last 25 years.) However, the fact that pedestrian injury is still the leading cause of death among one to14-year-olds shows that there is still some way to go. (In 2000, 38 child pedestrians died and about 1140 were hospitalised.) While the Indigenous infant mortality rate is also gradually declining (at about 3.3% per year) it remains 2.5 times that of other Australian infants.

Mental illness is a very important cause of disability in young children with about 12 per cent of children having a diagnosable mental illness at any one time; and this further increases in significance in adolescence / young adulthood. In the 15 to 25 year age group, 50% of all illness is caused by mental health, mainly anxiety and depression, and substance abuse issues. By the age of 25, three quarters of all long term mental health issues have emerged. Unfortunately, many of these young people do not have access to health care.

Mental illness in adults is also a significant contributor to childhood illness with the number of children on care and protection orders rising almost 50% between 1997 and 2003. In 2004 about 5 in 1000 children were in out-of-home care.

In 2018 about 27% of children were either overweight or obese and this hasn't changed over the last 10 years.

What childhood illnesses can to some extent be prevented?

Several of the major childhood illnesses, including neonatal causes, accidental injury and sudden infant death syndrome, can be significantly prevented. It is also worthwhile noting that the reason infectious disease contributes only 5.6% to total disease burden is that Australian children are immunized against most serious infections. Without immunization, this situation would be very different. Despite this, over 5,000 children suffer vaccine preventable illnesses in Australia each year, the most common being whooping-cough, measles and rubella.

Patents are often the first to notice developmental problems in their children and it is common for them to bring such concerns to a doctor’s attention. A separate table ( 'Developmental milestones in children' table.) provides a table detailing childhood developmental milestones.

The rest of this chapter deals with other preventable childhood illnesses, with special emphasis on parenting issues and mental health, an issue all parents need to address.

Modifiable Risk Factors - Burden of disease caused in Australians according to age and sex (2015)(% of total disease burden caused in age group) |

|||

| Males | % of disease burden in age group | Females | % of disease burden in age group |

| 0 to 15 year age group | 0 to 15 year age group | ||

|

|

|

|

| 15 to 24 year age group | 15 to 24 year age group | ||

|

|

|

|

1. Congenital abnormalities:

The causes for most congenital abnormalities are unknown. However, about 5 per cent are due to maternal illness, including diabetes and infections such as rubella, and drugs that cause foetal abnormalities (teratogenic drugs). Environmental substances, such as mercury, and nutrient deficiencies, especially folate, are also causes. The incidence of some congenital malformations can be reduced through neonatal diagnosis of the conditions and subsequent termination of the pregnancy, for example in Down syndrome. Reducing congenital abnormalities is covered in the section on preparation for pregnancy.

2. Neonatal causes:

The main causes of neonatal illness are low birthweight and birth trauma, including breathing problems at birth (asphyxia). Babies with a low birthweight (less than 2500 g) are more likely to suffer illness at the time of birth, such as infections and neurological complications, and are more likely to develop diseases, including high blood pressure and diabetes, in later life. The incidence of low birthweight can be significantly reduced by refraining from smoking and alcohol and eating a healthy diet while pregnant, and receiving good obstetric care. Similarly, good obstetric care is of paramount importance if birth trauma and asphyxia are to be prevented. Ensuring that an experienced and caring practitioner delivers the baby in a well resourced hospital is the best start a baby can receive. In childbirth, problems are not always predicable and can occur quickly. Home deliveries are just not as safe. Medical preparation for producing a healthy baby and mother needs to start prior to conception and this topic is covered in the section on preparation for pregnancy.

3. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is defined as the sudden death of a child under the age of 12 months where no reason can be found for the death. (A reason is only found in about 15% of such sudden deaths.) Most cases occur in the first six months of life and are due to the children smothering in their beds. It is an infrequent event with an overall incidence of about one in 1300 infants. The critical issue in reducing the incidence of SIDS to ensure that babies are placed on their backs when going to sleep and the 'Back to sleep' campaign that has promoted this practice has more than halved the incidence of this tragic event. Placement of infants on their stomach or on their side must be avoided always as it increases the risk of suffocation. Babies also need to be positioned so that they can not roll over on to their stomachs. This is best achieved by placing them with their feet at the foot of the cot and ensuring all bed clothes (blankets and sheets) are well tucked in.

The best mattress is a firm one with no side bumpers. There should be no loose bedding or other items in the cot including doonas, snuggle rugs, pillows, duvets, sheep skins and soft toys etc. These should be kept out of the cot. The infant should mot be overly wrapped and it is also best if the room is not too warm. It is best if twins sleep in separate cots. If they do sleep together, they should be placed with heads facing towards the centre with separate covers tucked in at each end.

Not smoking during pregnancy and not smoking near babies (especially if they are sleeping) is also a very important way to reduce the risk of SIDS. Sleeping with an infant on a sofa or a chair can increase the SIDS risk as can sleeping in bed with a baby and these practices should be avoided. Breastfeeding may reduce the incidence of SIDS. Using a dummy at sleeping time may also help reduce SIDS, although it is not critical and parents who have decided not to use them should probably not worry unless there is particular concern regarding the baby’s risk of SIDS.

Continually sleeping on their backs has led to an asymmetrical moulding of the head in some babies. To avoid this, it is important that babies are placed on their sides or front for some of the time when they are awake. The baby must be supervised (i.e. watched by a responsible person) when this is done and should not be left unattended in this position. A good time to do this is when either parent is playing with their baby.

Immunisation is not a cause of SIDS (or autysm).

As stated above, the adoption of the above recommendations has reduced the incidence of SIDS by about 62 per cent from 1990 to 2000 and it is still falling.

Apparent life-threatening events: Some infants experience what are termed 'Apparent life-threatening events', where the child is seen to be not breathing, often appears blue or pale, and may appear 'floppy'. Such events are associated with an increased risk of SIDS with a mortality rate of up to 10%. Infants who suffer such an episode should be immediately taken to a paediatric hospital (or other hospital where a paediatric hospital is not available) for assessment. (They are usually admitted to hospital.) All parents who have a child who has had one of these episodes should have formal training in CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation).

4. Mental disorders:

The influence of parental behaviour on children can not be underestimated. Good parenting techniques and refraining from substance abuse, especially alcohol, are major factors in producing healthy, well-adjusted children and can significantly reduce the incidence of mental illness in childhood. For example, parental conflict has been shown to impact negatively on childhood mental illness, causing fear, anger and stress. On the other hand, an encouraging parenting style using rewards and reinforcement has the opposite effect. Divorce and separation interestingly have a negative emotional and mental impact in the short term but in the long term children are not detrimentally affected. The topic of parenting is dealt with in more detail in the sections on anxiety and relationships.

5. Diet and obesity:

Excess energy (food) intake and physical inactivity are major problems for Australian children and are the cause of our childhood obesity epidemic. This topic is discussed in detail in the section on childhood obesity. Dietary deficiencies are uncommon in Australian children. The only exception is iron deficiency anaemia, which is responsible for just under two per cent of the total burden of disease and is more common in boys. List of foods rich in iron.

Check ups:

It is important to make sure that children, especially young children, are regularly checked for medical problems. Many childhood medical problems that can lead to significant disability are correctable if found early, including congenital hip dislocation, squints and hearing/speech abnormalities. This process starts in the hospital with baby checks and should be continued on a regular basis. Visits for routine immunisations are a good opportunity to have baby check-ups and to mention any concerns. Remember that parents know their child best and parents who are worried about their child for any reason should see their doctor and make sure their concerns expressed and understood.

Presented in the boxed section below is a timetable for addressing childhood and adolescent preventative health issues.

Timetable for addressing childhood and adolescent preventative health issues.

Early parenting issues:

- Early parenthood is a difficult period and it is common for parents to have difficulty coping. Parents who are worried about how they are coping should see their doctor before the problem becomes too serious. (Depression is a major problem at this time.) Any family member or friend who is concerned about the well-being or safety of a child or mother should seek help as soon as possible.

- Contraception needs to be discussed at the first postnatal GP visit.

Babies:

- The first post hospital GP check, usually done at about six weeks of age, is important for detecting congenital problems, including hip problems, heart murmurs, and undescended testes in boys. It is also a good time to check that blood tests taken in hospital for phenylketonuria, cystic fibrosis, hypothyroidism were normal. Very importantly, it is an opportunity to mention any concerns regarding the new baby, how things are going generally in the household. The baby’s weight gain is often a parental concern. Most babies gain about 200g to 250g of weight per week in the first four to six weeks and this gradually decreases so that the gain is about 150g to 200g per week by three months of age.

- Sudden infant death syndrome is an important concern in the first two years of life and particularly in the first six months. (See above.)

- Breast feeding is best but is often not easy and many mothers will need to supplement with formulas. Solids should be added from six months onwards. (There is evidence that babies can fail to thrive if solids are introduced later than six months.)

0 to 5 year olds

- Growth should be checked every three to six months in the first two years of life by measuring height, weight and head circumference. From 3 to 5 years of age, yearly growth checks should include height, weight and BMI (Body mass index).

- Developmental progress, including speech, hearing, sight and mobility, should be actively monitored by parents and it is often the case that patents are the first to notice developmental problems in their children. These abnormalities should be discussed with GPs, especially if there is uncertainly about whether an abnormality exists. (A table detailing developmental milestones appears in Appendix 4 and may help assist in this regard but talk with a medical practitioner too.) It is becoming more common practice to approach this task more formally by having parents fill in a Parents’ Evaluation of Development Status (PEDS) response form. These are completed in the presence of a health professional or a school or pre-school staff member who has knowledge of this diagnostic tool. Details regarding the tool, which was developed at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, can be found at the following website: http://www.rch.org.au/ccch/pub/index.cfm?doc_id=6472

- Squints (turned eyes) should searched for by parents and GPs from a very early age as successful treatment relies on early detection.

- Accident/injury prevention. (Discussed later in this section.)

- Dental care should include an annual visit to the dentist from three years of age. If children do not drink water supplemented with fluoride, parents should consider providing regular fluoride supplements.

- Sun protection is an important health issue from birth. Pre-schools and schools should have good sun protection policies, such as the no-hat-no-play rule, and promote education about sun protection. (See skin cancer section)

- Optimum nutrition and physical activity levels need to be encouraged.

- Immunisations (See immunization schedule)

6 to 14 year olds:

- Accident/injury prevention. (Discussed later in this section.)

- Assessment of growth progress through assessing height, weight and BMI should be done if there is concern about progress.

- Educational progress should be done at least yearly.

- Sun protection (See skin cancer section)

- Awareness of mental health problems, especially anxiety and depression, needs to be a priority in this age group. This issue is discussed in the section on mental health.

- Immunisations (See immunization schedule)

- Obesity and physical inactivity (See section on childhood obesity prevention.)

Adolescents

- Parents, GPs and other adults, including teachers and friends, need to be both observant and inquisitive so that any adolescent health problems can be found and addressed early on. Parents and schools need to be active in providing information to all adolescents about the following health issues and discussing appropriate preventative strategies. Parents should not assume that it will not happen to their child.

- Anxiety / Depression (see below) (See section on anxiety and depression in childhood and adolescence)

- Obesity and physical inactivity (See section on childhood obesity prevention.)

- Smoking (See section on smoking related disease.)

- Risk taking behaviours, including alcohol and other drug abuse.

- Social problems at home, including the risk of abuse.

- Teenage pregnancy (See section on teenage pregnancy prevention.)

How do GPs assess the psychological health of older children

Medical practitioners when seeing young people will usually use the opportunity to do a quick assessment of how the child is coping psychologically. This is done by asking questions in the 'HEADS' (or more correctly HEEADSSS) categories.

- H - Home

- E - Education

- E - Employment

- A - Activities

- D - Drugs (smoking, alcohol, recreational)

- S - Sexuality

- S - Suicide (depression)

- S - Safety

See separate sections for the following topics

Childhood Accident and Injury Prevention - Includes child abuse

Infectious disease prevention

Developmental milestones in children

Dental health

Preventing and addressing anxiety disorders in children - An important parenting issue

Driver safety and teenagers

Further information on child health and parenting

The Sydney Children's Hospitals Network (includes The Children’s Hospital at Westmead.)

This hospital network's web site (https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au) is a great source of information on children’s health topics. It provides fact sheets about many child health issues that are free and downloadable and lists books on most child health topics that have been assessed by members of the medical staff at the hospital. These books are available for purchase from the Kids Health Bookshop at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead (Phone 02 – 9845 3585) or they can be purchased via the ‘e-shop’ on the web site. Any profits go into supporting the work of the hospital.

Some suggested books on parenting babies and children

Every parent. A positive approach to children’s behaviour by Matthew R Sanders, PhD.

From Birth to Five Years Revised and Updated by Ajay Sharma and Helen Cockerill

Todler Taming by Dr Christopher Green (2014)

1-2-3 Magic: Effective Discipline for Children 2 to 12 by Thomas W. Phelan Ph.D.

More Secrets Of Happy Children by Steve Biddulph

Raising Kids- A parent’s survival guide by Charles Watson, Dr Susan Clarke and Linda Walton.

Is Your Child Ready for School? by Dr Sandra Heriot and Dr Ivan Beale

Bully Busting by Evelyn M. Field

Raising Boys in the 21st Century by Steve Biddulph

Raising Girls by Steve Biddulph

The Complete Secrets of Happy Children by Steve Biddulph

Fight Free Families by Dr Janet Hall

Your Child's Self Esteem by Dorothy Corkhille Briggs

The Whole-Brain Child by Drs Daniel J. Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson

Helping Your Anxious Child by Ronald Rapee PhD, Ann Wignall DPsych, Susan H Spence PhD, Vanessa Cobham PhD and Heidi Lyneham PhD

(All these books and many more appear in the ‘self esteem, behaviour and family life’ section of the books section in parents section of the Children’s Hospital at Westmead web site. https://kidshealth.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/bookshop-and-products) There is information about each book on the web site; just click over the title.) Better still, for parents able to visit the hospital, most of the books are available to view and there will be someone there to help with book selection.)

Some suggested books on parenting adolescents

Puberty boy by Geoff Price

Puberty girl by Shushann Movsessian

Skip the Drama by Dr Sarah Hughes

The puberty book by Wendy Darvill and Kelsey Powell

Teen esteem by Dr P. Palmer and M. Froehner

Don't let your emotions run your life for teens by Sheri van Dijk

What to do when your children turn into teenagers by Dr D. Bennett and Dr Leanne Rowe (This is a wonderful book that is unfortunately now out of print. Second hand copies may still be available.)

You can't make me by Dr D. Bennett and Dr Leanne Rowe

Most children suffer anxieties at some time and another book (not on the above list) that is very useful for parents is - Helping your anxious child. A step by step guide for parents. by Rapee, R., Spence, S., Cobham, V. and Wignall, A.New Harbinger, 2000.

I just want you to be happy. Preventing and tackling teenage depression. by Professors Leanne Rowe, David Bennett and Bruce Tonge. Published by Allen and Uwin, 2009.

The Resilience Doughnut parenting program to help build child resilience

The Resilience Doughnut Program is outlined in a book published by Lyn Worsley, which can be purchased through her website: www.lynworsley.com.au (The cost is about $30)

Triple P Positive Parenting Program

www.triplep.net.

Child and Youth Health

Parenting and child and youth health; links to research updates; telephone helps lines for parents and youth.

www.cyh.com

Further information on sexual health

Sexual health information

www.shinesa.org.au

Family Planning NSW

https://www.fpnsw.org.au

The Resource Center for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention web site

(A good USA site that provides information and skills for both adolescents and for educators about preventing unwanted teenage pregnancies.)

www.etr.org/recapp

Further reading regarding teenager sexual health

Sexwise by Dr Janet Hall. Published by Random House Australia.

(What every young person and parent should know about sex. Dr Hall empowers her readers by telling them the facts - and giving it to them straight.)

Unzipped by Bronwyn Donaghy. Published by Harper Collins

(A book that deals frankly and sympathetically with the crucial role that love and emotions play in every aspect of adolescent sexuality.)

Further titles regarding puberty and adolescent sexuality are available on the Children’s Hospital at Westmead web site. www.chw.edu.au/parents/books. (Both the above books are mentioned on this web site and are recommended by staff at this hospital.)